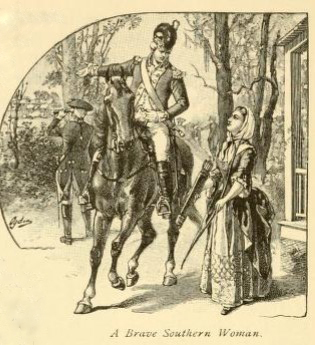

Women in Our History--Revolutionary War

|

| New Eclectic History of United States, 1890 Mary Elsie Thalheimer |

Eleanor Carothers Wilson--North Carolina

I am very proud to count a woman of singular energy of mind and courage, Eleanor Carothers Wilson of Steele Creek, Mecklenburg Co., North Carolina as my 5th great grandmother. A native of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, she was the wife of Robert “Old Robin” Wilson, and they moved their growing family to North Carolina about 1760. By the time of the American Revolution, this whole family was devoted to securing our liberty, with 7 of their 11 sons serving in various campaigns of the war. Two had earlier been captured at Charleston and later paroled, including my ancestor, Robert, Jr., and later Robert, Sr. and another son, carrying supplies to General Sumter at Camden, South Carolina, were also captured. While they were still in British hands, Cornwallis moved into the Charlotte area to forage and plunder the surrounding farms, taking control of the Wilson’s farm and house and requiring Mrs. Wilson to serve them.

Cornwallis thought he could prevail upon her to turn her family against the American cause by offering her sons places of rank in his army and promising to release her husband and son from the jail at Camden. He did not know the measure of the woman he was dealing with. Her reply has been recorded that not only would she not encourage her older sons to join his army, she and her younger sons would enlist under Sumter’s standard and show her husband and older sons how to fight and, if necessary, to die for their country.

A Washington, D.C. chapter of the DAR has been named in her honor.

NOTE: This information is from the book by Mrs. Elizabeth F. Ellet, _The Women of the American Revolution_, Volume III, pages 347-356, published by Baker and Scribner, New York, in 1845, with family information provided to her by Eleanor Wilson’s great-grandsons, Rev. T.W. Haynes of Charleston, SC and Milton A. Haynes of Williamson Co., TN.

Cyrus L. Hunter, gave a similar version, almost word for word, of these events in his book _Sketches of Western North Carolina_, written in 1877. No doubt Mr. Hunter got his information from Mrs. Ellet’s book.

Submitted by Kathryn Schultz

Anna Asbury Stone

|

| Permission granted by Linda (Adams) LeBarre, Find a Grave ID 47010459 |

On the approach of the British Army, Congress had fled from Philadelphia and taken refuge in York, Pennsylvania, where they spent the time in idleness as far as anything for the relief of the troops was concerned. In spite of the privations and suffering of the soldiers, in spite of earnest letters and fervent appeals from General Washington, the winter was passed in scheming and banqueting, and nothing was done to relieve the desperate situation. General Gates, elated by the surrender of General Burgoyne, aspired to the position of Commander-in-Chief, and with his friends left nothing undone to influence Congress to depose General Washington.

Among the faithful soldiers who spent that dreary winter with Washington at Valley Forge was Benjamin Stone, a young Baptist clergyman, who had just been ordained to preach. At the first call for military service he took his young wife and their three little ones to home of her father near Culpepper, Virginia, and enlisted to fight for liberty; first as a member of the Culpepper Minute Men under Colonel Marshall, and later in a South Carolina Regiment under General Francis Marion. Three brothers of Anna Asbury Stone were also at Valley Forge, John, George, and the youngest, Jeremiah, who before the war was over, had made the supreme sacrifice.

Patrick Henry was at this time Governor of Virginia, and his loyalty to the cause and to the Commander-in Chief, never wavered. So, it was to him that General Washington turned for help and sent a special messenger to him to inform him of the dreadful conditions at the camp, asking that he strive to the uttermost to arouse Congress to immediate action. As the messenger passed down through the valley of Virginia reports spread of the privations and suffering at Valley Forge. The news brought grief to these homes for these soldiers were their very own fathers, sons, brothers and husbands. There was weeping, praying and planning. In the home of George Asbury, as in others, the painful news carried deep distress, but there the tears and prayers soon blossomed into action.

Anna Asbury Stone decided to carry what relief she could to Valley Forge. It was a journey of no ordinary difficulty—a journey of nearly two hundred and fifty miles. It must be made on horse-back, in the dead of winter, and by unfrequented roads and bypaths through the mountains for fear of capture by the Indians or the British. But a woman’s will inspired by a woman’s love and upheld by a woman’s faith can work wonders; and the loyal, determined little wife set out on her long and perilous journey. Accustomed to riding from childhood and mounted on her own fine saddle horse, heavily laden with supplies, blankets, clothing and food, she started forth, leaving her three babies to the care of her father and mother, and the negro mammy.

The journey would require at least three weeks to go and return, but Anna Asbury Stone’s courage was equal to anything for her husband and brothers. Nothing unusual happened until she reached the temporary capital at York, Pa. Here she stayed all night at the home of a cousin, Thomas Burler. Here, hearing of her destination, William Harrison was sent to her with a letter which he asked her to deliver personally into the hands of the Commander-in-Chief, saying that it was very important. Next morning she was on her way at sunrise.

After two hours riding, she was startled to see a horseman approaching from a crossroad and bar her way. He said that William Harrison had changed his mind and wished that letter she was carrying returned at once. Anna, who had an almost uncanny gift of telepathy looked at him a moment with her honest, gray eyes, than struck Nelly (her horse) with her whip and was off like the wind. That night she stayed at the home of a loyal farmer, and left as soon as it was light. During the morning she heard hoof-beats behind her, and looking back saw her tormentor of the day before, coming rapidly, but Nelly was fast and sure-footed and carried her brave mistress safely to the American picket lines, where she explained her mission, and was conducted to headquarters. While she was walking her horse slowly, suddenly Nelly threw up her head and whinnied loudly. One of the group of soldiers quickly turned at the familiar sound and ran at once to the side of his brave little wife, surprised beyond measure. Together they went to Washington’s headquarters where Anna had the pleasure of placing her important letter in the hands of the great Commander-in-Chief.

It brought him news which enabled Washington to thwart the plots of his enemies. General Washington thanked her warmly and insisted that she remain in Camp until the following Monday, when he was sending a detail of soldiers to meet his wife at Alexandria, saying that Mrs. Stone could travel under their protection, and that he would send her husband as one of the soldiers. The stocking of salt which had been part of her load, was given to General Washington, Benjamin insisting that her could not enjoy what his General did not have, and the camp had been without salt for some time. That Sunday in camp was a day never to be forgotten. Anna and her minister husband spent the day visiting the sick and dying in the rude log cabins bringing what cheer they could. The journey lasted until late Saturday night when the lights of home shone out a welcome to the plucky, weary, little woman.

Harriett Lura Bassett Stone,

Historian

A Cambridge, Ohio chapter of the DAR has been named in her honor.

Submitted by Winona Laird

Comments

Post a Comment