William Jackson Myers, Moving West

William Jackson Myers, Moving West

By Janet O'Conor Camarata

William Terry Myers, nicknamed

“Blackie” in his later years, was born December 7, 1861 In Terre Haute, Vigo

County, Indiana at the beginning of the Civil War. He was the second son of

William Jackson Myers and Mary Etta “Met” (Asher) Myers. William Jackson Myers and his parents were

originally from the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia and had moved west, sometime

in the early 1840s, settling in south central Indiana.

By 1860, William Jackson Myers

was living in Cloverdale Township, Putnam County, Indiana. He married “Met”

Asher on April 30, 1857 in Owen County and shortly thereafter, moved to Clay

County where his eldest son was born. When the war began in Indiana on April

12, 1861, William Jackson Myers was 31 years old living in Harrison Township,

Vigo County, northwest of Terre Haute. William Jackson chose not to volunteer

to serve in the Civil War. By 1862, a draft was established, and quotas were

set by the state government. At first, volunteers for the Union Army were

plentiful enough to fill the quota, so no draft was implemented in Vigo County.

A total of 4,445 men served in all branches of the war, both Union and

Confederate, from the Vigo County. By the time the war ended in Indiana on

April 9, 1865, William was the father of three children, the eldest son, Allen

J.; second son, William Terry and daughter, Louisa Myers.

It was time to leave

Indiana. The end of the war affected many economically and politically.

Returning soldiers were looking for work and returning to their homes.

Conflicts and tensions continued to resurface between Union and Confederate

returnees. Ads appeared in local

newspapers like the Wabash Daily Express and the Terre Haute Daily Morning

Journal offering good terms and favorable loans for all kinds of property in

Iowa and Missouri. William Jackson Myers, a farmer without land of his own made

the decision to leave Indiana with his young family. He traveled with his

wife’s parents, Lewis and Allie (Brown) Asher and their 13 children.

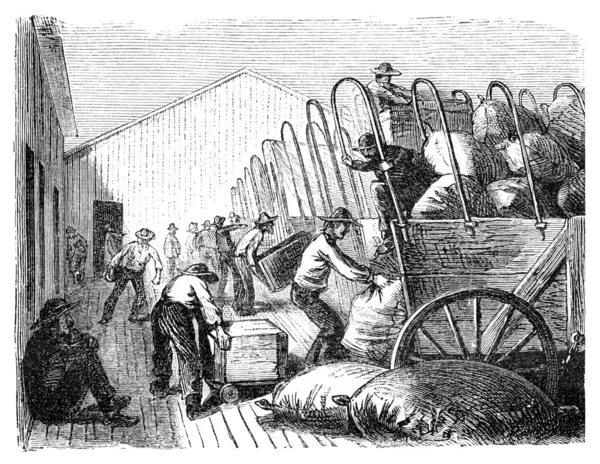

He purchased a covered wagon

and an ox team strong enough to pull it on their journey west. The sturdy covered wagons were known as

prairie schooners or “western wagons.” They had flat bottoms and lower sides

than the original Conestoga wagons of Virginia. The white covered canvas made

the wagons look like sailing ships from the distance, earning them the

“schooner” name. The Myers and Asher families left Terre Haute in the summer of

1865 and moved across the prairie, following the National Road, the major route

for western expansion, passing established towns and farms from Terre Haute to

Vandalia, Illinois, 100 miles. From

here they traveled north to a point on the Mississippi River where they could

float across on a flat-boat ferry, a shallow rectangular watertight barge or

“mud scow” with gently sloping ends, strong enough to load and unload a wagon,

ox team, a family and all their family goods.

Using the current for power, they floated downriver and maneuvered with

oars until they reached the west side of the river. Their journey continued

until they reached their destination in north central Missouri, first settling

in Grundy County, Missouri, 350 miles and 35 miles from the Iowa border. It

took them about six weeks to make the journey.

The William Jackson Myers family settled on Asher Ford southwest of Denver, Gentry County in the north

central area of Missouri. Although the region was first settled more than

thirty years before, much of it was still available and heavily timbered,

especially in oak and walnut. They cleared the land, built their homes, and

began farming the land. William Jackson Myers died 23 years later, July 17,

1908 from complications of “old age” at the age of 78. He was buried in Maple

Grove Cemetery in Trenton, Grundy County, Missouri with a hand-cut stone

reading, “Wm. J. Myers, 84y. Born VA. h/o Mary Etta (ASHER) 30 Apr 1857 in Owen

Co., IN. Died 1908.” William Jackson Myers lived life to the fullest. His

headstone symbolizes the permanence of the family’s memory of their ancestor.

Comments

Post a Comment